Why prototyping

All buildings are predictions.

All predictions are wrong— Stewart Brand How Buildings Learn

We designers make predictions about the user, the device, and the environment all the time. Even the most battle-scarred designers make poor predictions that result in painful user experiences.

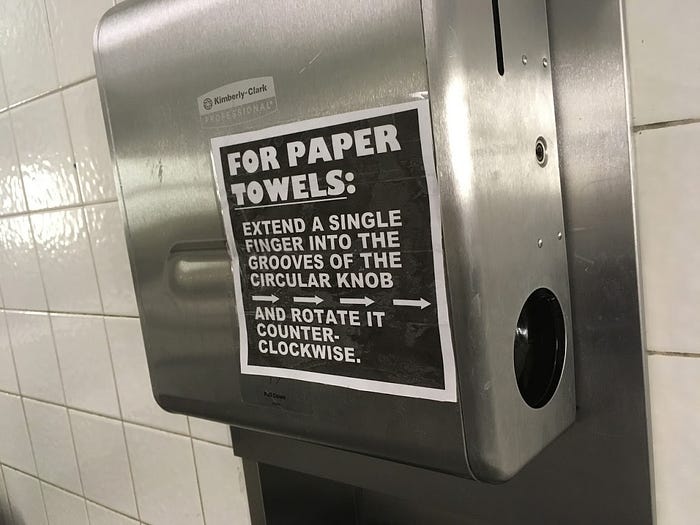

What predictions did the designer make about this towel dispenser and its users? Note a second sticker near the bottom that says “pull down”.

Prototyping could have revealed some of the wrong predictions about this towel dispenser and its users — 1) do people always pull the towel downward? 2) does pulling one piece of towel always reveal the next? 3) do people know where the knob is and what it does? 4) when people turn the knob, do they turn it clockwise or counterclockwise? Prototyping saves the day by catching errors in predictions like these before we’ve gone too far. With the help of prototyping, we can:

Fail fast, fail cheap

Prototypes are built with materials that are cheap and easy to modify or replace. Antoni Gaudí’s prototype of Sagrada Familia was simply made of strings weighted down with birdshot. The everyday material enabled Gaudí to instantly adjust the curvature of the vaulted ceiling in his model. He just needed to increase or reduce the birdshot weight. The beauty of the final product was marveled by millions of visitors every year.

The prototype informed the design of the awe-inspiring ceiling of Sagrada Familia [1] [2]

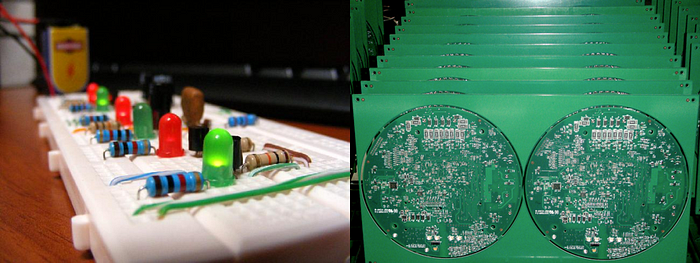

Whenever a change in design is prohibitively expensive, prototyping helps in reducing the cost of development. Electronic engineers prototype on breadboards or micro controllers like Raspberry Pi that cost a fraction of the real thing. Each design flaw discovered during the prototyping translates to millions of dollars saved in marketing failures, recalls, and lawsuits.

From the breadboard prototype to the printed circuit board [3] [4]

Select the best from the pool

Thanks to their low cost, multiple prototypes can be built and tested at the same time, so the designers can select the best from the pool. This is effectively artificial selection.

Think of genetic engineers as designers of species. Instead of trying one crossbreed or one genetic mutation on one individual at a time, they always test on a population, maximizing the likelihood of finding desirable traits. It is the low cost of reproducing each additional individual that makes the selection possible on a large scale.

Scientists perform genetic selection at scale [5]

We see a similar strategy in quantitative trading where the investors use a computer algorithm to determine when to buy or sell stocks. Before they trust a new algorithm with millions of dollars, the investors “prototype” the algorithm by auditing its performance for a few months with a hypothetical investment. Since the cost of adding one algorithm to the performance audit is almost zero, the investors can hold worldwide competitions like this to maximize the likelihood of finding the best algorithm.

Bring in the reality

No matter how good a piece of design looks on paper, it may not work as expected in the real world due to added complexity and unexpected conditions. Testing a roughly-made prototype in the real environment can be more productive than pursuing the perfect design on paper.

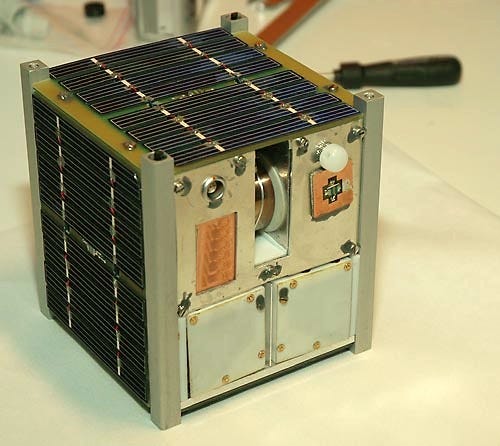

The space industry probably requires the most rigorous design on paper. Engineers spend sleepless nights solving equations and running simulations. Risks are avoided by all means because failures cost billions. When CubeSat, the 10×10×10 cm cubic satellite, entered the industry, it brought down the cost of each unit so much that risk-taking suddenly became affordable. Engineers would collect real-world data from the launch of a prototype, improve the design using the data, and launch the next iteration within months.

A CubeSat built by Norwegian university students [6]

The prototypes exposed the design to real-world conditions such as wind, temperature, and cosmic rays, which are almost impossible to simulate with computer aided design software. Powered by the learning from these real-world lessons, people turned what was a once a prohibitive rocket science into fun and educational crowd funding projects like this. Sky is no longer the limit.

A similar prototyping practice had been widely adopted in the automobile industry where they call prototypes “pre-production” cars. Those camouflaged prototypes allowed car makers to evaluate the handling, comfort, and performance of a design with real drivers and passengers on real roads under real weather conditions, but without the overhead in building complete production lines or the need to meet all industry regulations. Using the data collected from the prototypes, car makers can address issues that are difficult to identify through software simulations.

A pre-production prototype car in road test [7]